New UN Climate Damage Tax: If you’ve been wondering, “Who should pay for all this climate chaos?” you’re not alone. From devastating wildfires in California to floods sweeping through Pakistan and rising sea levels swallowing coastlines, the costs of climate change are adding up. And fast. That’s why global leaders and climate justice advocates are rallying around a bold new idea — a UN climate damage tax targeting the fossil fuel companies most responsible for the climate crisis. The proposal could shake up the international climate finance system and bring billions — even trillions — in new funds to help countries bounce back from disasters and prepare for a hotter, riskier world. This article gives you the full rundown: what this tax is, how it would work, who supports it, and what it means for the future of climate accountability.

Table of Contents

New UN Climate Damage Tax

The idea of a climate damage tax on fossil fuel companies is simple but powerful: Make the companies most responsible for climate change pay into a fund that helps the world cope with its effects. Whether it’s floods in Pakistan or hurricanes in Florida, the costs of climate damage are soaring. The proposed tax could provide predictable, fair, and much-needed funding, all while sending a clear message — climate justice is no longer optional. As the world gathers at climate summits and tax conventions, the question isn’t just can we implement a global polluter tax — it’s will we do what’s fair?

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Proposal Name | UN Climate Damage Tax / Polluter Pays Surtax |

| Targeted Companies | Top fossil fuel producers (oil, gas, coal) |

| Estimated Revenue Potential | Up to $900B – $1.08T over 5 years |

| Use of Funds | Disaster recovery, climate adaptation, just transition |

| Public Support | 80% globally support taxing fossil companies |

| Discussed At | UN Tax Treaty talks, COP30, UNFCCC negotiations |

| Official Info Source | UN Climate Finance Portal |

What Is the New UN Climate Damage Tax?

The UN Climate Damage Tax is a proposed global tax on fossil fuel companies — especially the biggest polluters. The idea is to hold them financially accountable for the harm caused by decades of greenhouse gas emissions. The money collected would go into climate funds, especially the Loss and Damage Fund, to support nations hit hardest by climate disasters.

This isn’t about punishing companies just to punish them — it’s about fairness and responsibility. The idea is built on the “polluter pays” principle: if your business model caused the problem, you should help cover the cost of fixing it.

We’re talking about charging companies like ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, and others — many of whom have made record-breaking profits in recent years — to fund rebuilding efforts after typhoons, wildfires, and sea level rise threaten lives, homes, and cultures.

Why Is This New UN Climate Damage Tax Being Proposed Now?

Several converging reasons have pushed this idea into the global spotlight:

- Climate impacts are getting worse.

Disasters are hitting harder and more frequently — and the bill keeps growing. - The existing climate finance system isn’t cutting it.

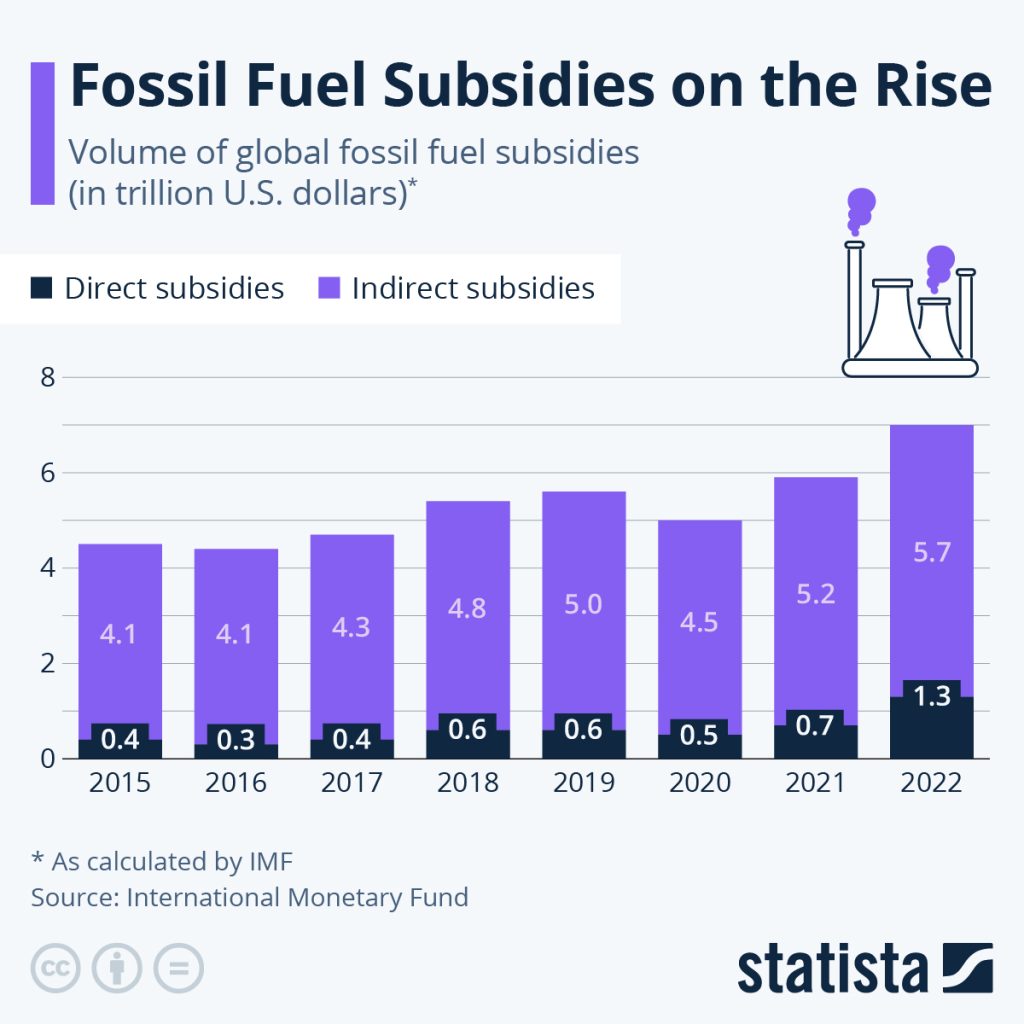

Rich nations have long promised $100 billion a year in climate support to developing countries but have consistently fallen short. - Polluters are still profiting.

In 2022 and 2023, oil giants posted windfall profits. ExxonMobil alone earned $56 billion in 2022, its most profitable year ever. Meanwhile, people in low-lying island nations are watching their homelands disappear. - Public demand for fairness.

Surveys show overwhelming global support for taxing oil and gas companies to fund climate relief — especially when regular folks are already struggling with high prices and disaster recovery. - The UN Tax Convention and COP30 offer new avenues.

These high-level negotiations give countries a chance to agree on bold, coordinated approaches to global challenges.

Real-World Example: The Pakistan Floods

To make this real, consider what happened in Pakistan in 2022. Catastrophic monsoon floods submerged a third of the country, displaced 33 million people, and caused $30 billion in damage. Yet Pakistan contributes less than 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The country appealed for emergency aid, but international response was sluggish. A climate damages tax could provide reliable, fast, and fair funding to help rebuild and prepare for future risks — instead of relying on slow-moving donations or loans that push countries deeper into debt.

How Would the New UN Climate Damage Tax Work?

There are two primary proposals on the table, each offering different ways to calculate what fossil fuel companies would owe.

1. Polluter Profits Surtax

This model taxes excess profits — revenues above a certain baseline.

- Suggested surtax: 20% on windfall profits

- Target: Top 100 fossil fuel companies

- Estimated revenue: $900 billion to $1.08 trillion over 5 years

This surtax would be similar to what countries like the UK and Italy have already applied to domestic oil and gas companies. But the UN version would be international and coordinated, with funds pooled and redistributed fairly.

2. Climate Damages Tax (CDT)

This version places a levy on fossil fuel extraction itself — per barrel of oil, per ton of coal, or per cubic meter of natural gas. It’s based on the carbon content of the fuel.

- Initial tax: ~$5/ton CO₂ equivalent

- Annual increase: ~5%

- Revenue grows with production and time

The CDT is supported by groups like Greenpeace, Climate Justice Now, and Global Witness, who argue it sends a stronger price signal to transition away from fossil fuels entirely.

Where Would the Money Go?

The revenue from the climate damage tax would be earmarked for climate justice purposes, especially in countries most affected by climate change but least responsible for causing it.

Potential recipients and uses:

- Loss and Damage Fund (created at COP27)

- Adaptation projects (sea walls, drought-resistant crops, early warning systems)

- Climate disaster response (evacuation infrastructure, medical aid, rebuilding)

- Just transition programs (job training for workers in fossil fuel sectors)

Importantly, this isn’t meant to replace existing climate pledges — it’s additional funding to fill in major gaps.

A Broader Shift in Climate Finance

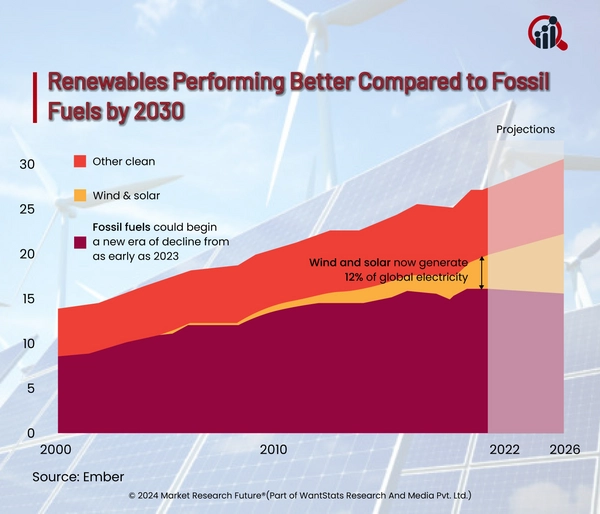

This tax is part of a larger push to transform global climate finance. That means:

- Moving from charity to justice

- Relying on predictable revenue, not vague pledges

- Making the largest historical emitters shoulder their share of the burden

As a result, the proposal has been called “one of the most morally and economically sound ideas in climate policy today.”

Who Supports This New UN Climate Damage Tax?

Civil society groups:

Greenpeace, Oxfam, Eurodad, Climate Action Network, and more.

Developing nations:

Countries from Africa, the Pacific Islands, and South Asia — often hit hardest by climate disasters — have expressed support for bold funding mechanisms.

Public opinion:

A 2023 global survey conducted by Oxfam found that 8 out of 10 people support taxing oil and gas companies to help fund climate recovery efforts.

Former world leaders:

More than 100 ex-heads of state, including former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, signed an open letter backing the proposal.

Who Opposes It — and Why?

Not surprisingly, fossil fuel companies and some governments have expressed concerns, arguing that:

- It could destabilize global energy markets

- Costs may be passed on to consumers through higher energy prices

- It might be legally complex to implement internationally

Others worry that a poorly designed tax could discourage investment in energy infrastructure — though many climate economists argue the transition to clean energy is inevitable and must be planned fairly.

What Makes This Different from Carbon Pricing?

While carbon pricing (like carbon taxes or emissions trading) is focused on changing behavior through economic incentives, the climate damage tax is more about paying for harm already done.

Think of it like this:

- Carbon pricing = a parking meter that charges you to discourage illegal parking

- Climate damage tax = the fine you pay if you crash into someone’s house

Both are useful. But they serve different purposes.